Bolesław III Wrymouth

| Bolesław III Wrymouth | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Poland | |

|

|

| Portrait by Jan Matejko. | |

| Reign | 1107–1138 |

| Born | August 20, 1086 |

| Birthplace | Poland |

| Died | October 28, 1138 (aged 52) |

| Place of death | Sochaczew, Poland |

| Buried | Masovian Blessed Virgin Mary Cathedral, Płock, Poland |

| Predecessor | Władysław I Herman |

| Successor | Władysław II the Exile |

| Wives | Zbyslava of Kiev Salomea of Berg |

| Offspring | With Zbyslava: Władysław II the Exile A son A daughter [Judith?], Princess of Murom With Salomea: Leszek Ryksa, Queen of Sweden A daughter, Margravine of Nordmark Sophie Casimir Gertruda Bolesław IV the Curly Mieszko III the Old Dobroniega, Margravine of Lusatia Judith, Margravine of Brandenburg Henry Agnes, Grand Princess of Kiev Casimir II the Just |

| Royal House | Piast |

| Father | Władysław I Herman |

| Mother | Judith of Bohemia |

Bolesław III Wrymouth (Polish: Bolesław III Krzywousty) (20 August 1086[1][2] – 28 October 1138) was Duke of Poland from 1102 until 1138. He was the only child of Duke Władysław I Herman and his first wife Judith, daughter of Vratislaus II of Bohemia.

Bolesław spent his early adulthood fighting his older half-brother Zbigniew for domination and most of his rule attending to the policy of unification of Polish lands and maintaining full sovereignty of the Polish state in the face of constant threat from expansionist eastern policy of the Holy Roman Empire and her allies, most notably Bohemia. Bolesław III, like Bolesław II the Bold, based his foreign policy on maintaining good relations with neighboring Hungary and Kievan Rus, with whom he forged strong links through marriage and military cooperation. Another foreign policy goal was the gain and conversion of Pomerania, which he accomplished by adding most of Pomerania to his domains by 1102-1122. Bolesław III also upheld the independence of the Polish archbishopric of Gniezno. He strengthened the international position of Poland by his victory over the German Empire in the Holy Roman-Polish War of 1109. He was also able to enlarge the country's territory. Despite undoubted successes, Bolesław III Wrymouth committed serious political errors, even against Zbigniew of Poland, his half-brother. The crime against Zbigniew and his penance for it show Bolesław’s great ambition as well as his ability to find political compromise. His last, and perhaps the most momentous act, was his will and testament known as "The Succession Statute" in which he divided the country among his sons, leading to almost 200 years of feudal fragmentation of the Polish Kingdom. Nevertheless, Bolesław became a symbol of Polish political aspirations until well into 19th century.

Contents |

Life

Birth and childhood

In 1086 the coronation of Vratislav II as King of Bohemia, and his alignment with László I, King of Hungary, threatened the position of the Polish ruler, Duke Władysław I Herman.[3][4] Therefore that same year Władysław I was forced to recall from Hungarian banishment the only son of Bolesław II the Bold and a rightful heir to the Polish throne, Mieszko Bolesławowic. Upon his return young Bolesławowic accepted the over-lordship of his uncle and gave up his hereditary claim to the crown of Poland in exchange for becoming first in line to succeed him.[5] In return, Duke Wladyslaw I Herman granted his nephew the district of Kraków.[6] The situation was further complicated for Władysław I Herman by a lack of a legitimate male heir, as his first-born son Zbigniew came from a union not recognized by the church.[7][8] With the return of Mieszko Bolesławowic to Poland, Władysław I normalized his relations with the kingdom of Hungary as well as Kievan Rus (the marriage of Mieszko Bolesławowic to a Kievan princess was arranged in 1088).[9] These actions allowed Herman to strengthen his authority and alleviate further tensions in international affairs.[10]

Lack of a legitimate heir, however, remained a concern for Władysław I and in 1085 he and his wife Judith of Bohemia sent rich gifts, among which was a life size statue of a child made of gold, to the Benedictine Sanctuary of Saint Giles[11] in Saint-Gilles, Provance begging for offspring.[12][13] The Polish envoys were led by the personal chaplain of Duchess Judith, Piotr.[14]

By 1086 Bolesław was born. Three months after his birth, on 25 December, his mother died. In 1089 Władysław I Herman married Judith of Swabia who was renamed Sophia in order to distinguish herself from Władysław I's first wife. Judith of Swabia was a daughter of Emperor Henry III and widow of Solomon of Hungary. Through this marriage Bolesław gained three or four half-sisters, and as a consequence he remained the only legitimate son and heir.

Following Bolesław’s birth the political climate in the country changed. The position of Bolesław as an heir to the throne was threatened by the presence of Mieszko Bolesławowic, who was already seventeen at the time and was furthermore, by agreement with Herman himself, the first in line to succeed. In all likelihood it was this situation that precipitated the young prince Mieszko’s demise in 1089.[15] In that same year Wladyslaw I Herman’s first-born son Zbigniew was sent out of the country to a monastery in Quedlinburg, Saxony. This suggests that Wladyslaw I Herman intended to be rid of Zbigniew by making him a monk, and therefore depriving him of any chance of succession.[16][17] This eliminated two pretenders to the Polish throne, secured young Bolesław’s inheritance as well as diminished the growing opposition to Wladyslaw I Herman among the nobility.[18] Shortly after his ascension, however, Władysław I Herman was forced by the barons to give up the de facto reins of government to Count Palatine Sieciech. This turn of events was likely due to the fact that Herman owed the throne to the barons, the most powerful of whom was Sieciech.[19] It is believed that Judith of Swabia was actively aiding Sieciech in his schemes to take over the country and that she was a mistress of the Count Palatine.[19][20]

In 1090 Polish forces under Sieciech's command, managed to gain control of Gdańsk Pomerania, albeit for a short time. Major towns were garrisoned by Polish troops, and the rest were burned in order to thwart future resistance. Several months later, however, a rebellion of native elites led to the restoration of the region’s independence from Poland.[21] The following year a punitive expedition was organized, in order to recover Gdańsk Pomerania. The campaign was decided at the battle of the Wda River, where the Polish knights suffered a defeat despite the assistance of Bohemian troops.[22]

Prince Bolesław’s childhood happened at a time when a massive political migration out of Poland was taking place,[23] due to Sieciech’s political repressions.[24][25] Most of the elites who became political refugees found safe haven in Bohemia. Another consequence of Sieciech’s political persecution was the kidnapping of Zbigniew by Sieciech’s enemies and his return from abroad in 1093.[25] Zbigniew took refuge in Silesia, a stronghold of negative sentiment for both Sieciech as well as his nominal patron Władysław I Herman.[25][26] In the absence of Sieciech and Bolesław, who were captured by Hungarians and kept captive, Duke Władysław I then undertook a penal expedition to Silesia, which was unsuccessful and subsequently obliged him to recognize Zbigniew as a legitimate heir.[25] In 1093 Władysław I signed an Act of Legitimization which granted Zbigniew the rights of descent from his line. Zbigniew was also granted the right to succeed to the throne. Following Sieciech and Bolesław’s escape from Hungary, an expedition against Zbigniew was mounted by the Count Palatine. Its aim was to nullify the Act of Legitimization. The contestants met at the battle of Goplo in 1096, where Sieciech’s forces annihilated the supporters of Zbigniew. Zbigniew himself was taken prisoner, but regained his freedom a year later, in May 1097, due to the intervention of the bishops.[27][28] At the same time his rights, guaranteed by the Act of Legitimization, were reinstated.[29]

Simultaneously a great migration of Jews from Western Europe to Poland began circa 1096, around the time of the First Crusade. The tolerant rule of Władysław I Herman attracted the Jews who were permitted to settle throughout the entire kingdom without restrictions. The Polish prince, took great care of the Hebrew Diaspora, as he understood its positive influence on the growth of the country’s economy.[30] The new Jewish citizens soon gained trust of the gentiles during the rule of Bolesław III.

Fight against Sieciech

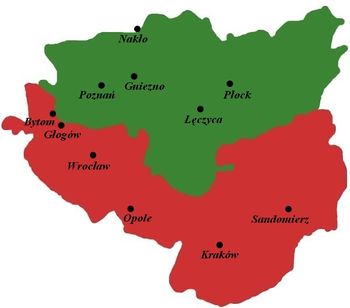

In view of his father’s disapproval, and after discovering the plans of Sieciech and Duchess Judith-Sophia to take over the country Zbigniew gained an ally in the young prince Bolesław. Both brothers demanded that the reins of government should be handed over to them. It is difficult to believe, however, that Bolesław was making independent decisions at this point as he was only 12 years of age. It is postulated that at this stage he was merely a pawn of the Baron’s power struggle. Władysław I Herman, however, agreed to divide the realm between the brothers,[31] each to be granted his own province while the Duke - Władysław I himself – kept control of Mazovia and its capital at Plock. Władysław also retained control of the most important cities i.e. Wroclaw, Krakow and Sandomierz.[32][33] Zbigniew’s province encompassed Greater Poland including Gniezno, Kuyavia, Leczyca Land and Sieradz Land. Bolesław’s territory included Lesser Poland, Silesia and Lubusz Land.[34]

The division of the country and the allowance of Bolesław and Zbigniew to co-rule greatly alarmed Sieciech, who then began preparing to dispose of the brothers altogether. Sieciech understood that the division of the country would undermine his position.[35] He initiated a military settlement of the issue and he gained the Duke’s support for it. The position of Herman is seen as ambiguous as he chose to support Sieciech’s cause instead of his sons'.[36] In response to Sieciech’s preparations Bolesław and Zbigniew entered into an alliance. This took place at a popular assembly or Wiec organized in Wroclaw by a magnate named Skarbmir. There it was decided to remove the current guardian of Bolesław, a noble named Wojslaw who was a relative of Sieciech, and arrange for an expedition against the Palatine. Subsequently, in 1099, the armies of Count Palatine and Duke Herman encountered the forces of Zbigniew and Bolesław near Zarnowiec by the river Pilica. There the Rebel forces of Bolesław and Zbigniew defeated Sieciech's army, and Władysław I Herman was obliged to permanently remove Sieciech from the position of Count Palatine.

The rebel forces were then further directed towards Sieciechów, where the Palatine took refuge. Unexpectedly, Duke Władysław came to the aid of his besieged favorite with a small force. At this point, the Princes decided to depose their father. The opposition sent Zbigniew with an armed contingent to Masovia, where he was to take control of Płock, while Bolesław was directed to the South. The intention was the encirclement of their father, Duke Władysław I. The Duke predicted this maneuver and sent his forces back to Masovia. In the environs of Płock the battle was finally joined and the forces of Władysław I were defeated. The Duke was thereafter forced to exile Sieciech from the country. The Palatine left Poland around 1100/1101. He was known to sojourn in the German lands. However, he eventually returned to Poland but did not play any political role again. He may have been blinded. On the other hand, Władysław I Herman died on 4 June 1102.

Duke of Poland

Struggle for the Dominion (1102-1106)

Following Duke Władysław I Herman’s death the country was divided into two provinces, each administered by one of the late duke’s sons. The extent of each province closely resembled the provinces that the princes were granted by their father three years earlier, the only difference being that Zbigniew also controlled Mazovia with its capital at Płock, effectively ruling the northern part of the kingdom, while his younger half-brother Bolesław ruled its southern portion.[37] In this way two virtually separate states were created.[38] They conducted separate policies internally as well as externally. They each sought alliances, and sometimes they were enemies of one another. Such was the case with Pomerania, towards which Bolesław aimed his ambitions. Zbigniew, whose country bordered Pomerania, wished to maintain good relations with his northern neighbor. Bolesław, eager to expand his dominion, organized several raids into Pomerania and Prussia[39]. In Autumn of 1102 Bolesław organized a war party into Pomerania during which his forces sacked Białogard[40]. As reprisal the Pomeranians sent retaliatory war parties into Polish territory, but as Pomerania bordered Zbigniew’s territory these raids ravaged the lands of the prince who was not at fault. Therefore in order to put pressure on Bolesław, Zbigniew allied himself with Borivoj II of Bohemia, to whom he promised to pay tribute in return for his help.[41] By aligning himself with Bolesław’s southern neighbor Zbigniew wished to compel Bolesław to cease his raids into Pomerania. Bolesław, on the other hand, allied himself with Kievan Rus and Hungary. His marriage to Zbyslava, the daughter of Sviatopolk II Iziaslavich in c.1103, was to seal the alliance between himself and the prince of Kiev. However, Bolesław's first diplomatic move was to recognize Pope Paschal II, which put him in strong opposition to the Holy Roman Empire. A later visit of papal legate Gwalo, Bishop of Beauvais brought the church matters into order, it also increased Bolesław's influence.[42]

Zbigniew saw the marriage of Bolesław to a princess from Rus' and an alliance with Kiev as a serious threat. He therefore prevailed upon his ally, Borivoj II of Bohemia, to invade Bolesław’s province. Bolesław retaliated with expeditions into Pomerania in 1104-1105, which brought the young prince not only loot, but also effectively disintegrated the alliance of Pomeranians and Zbigniew.[43] Bolesław’s partnership with King Coloman of Hungary, whom he aided in gaining the throne, bore fruit in 1105 when they successfully invaded Bohemia. Also in 1105, Bolesław entered into an agreement with his stepmother Judith of Swabia, the so called Tyniec Accord. According to their agreement, in exchange for a generous grant, the prince was guaranteed Judith's neutrality in his political contest with Zbigniew.[44]

In 1106 Bolesław managed to bribe Borivoj II of Bohemia and have him join his side of the contest against Zbigniew. In that same year Bolesław formally allied himself with Coloman of Hungary. During a popular assembly, attended by both princes, it was agreed that none of the brothers would conduct war, sign peace treaties, or enter into alliances without the agreement of the other. This created a very unfavorable situation for Bolesław, and in effect it led to civil war, with over-lordship of entire country at stake. With the help of his Kievan and Hungarian allies Bolesław attacked Zbigniew’s territory. The allied forces of Bolesław easily took control of most important cities including Kalisz, Gniezno, Spycimierz and Łęczyca, in effect taking control of half of Zbigniew’s lands. A peace treaty was signed at Łęczyca in which Zbigniew officially recognized Bolesław as High Duke of all Poland. However, he was allowed to retain Masovia as a fief.[45]

Sole Ruler of Poland

In 1107 Bolesław III along with his ally King Coloman of Hungary, invaded Bohemia in order to aid Svatopluk the Lion of Bohemia in gaining the Czech throne. The intervention in the Czech succession was meant to secure Polish interests to the south. The expedition was a full success. On 14 May 1107 Svatopluk was made Duke of Bohemia, in Prague.[46]

Later that year Bolesław undertook a punitive expedition against his brother Zbigniew. The reason for this was that Zbigniew did not follow the orders of Bolesław III and did not burn down the fort of Kurów.[47] Another reason was that Zbigniew did not keep his duty as a vassal and did not provide military aid to his lord, Bolesław III, for a campaign against the Pomeranians. In the winter of 1107-1108 with the help of Kievan and Hungarian allies, Bolesław III began a final campaign to rid himself of Zbigniew. His forces attacked Mazovia, and quickly forced Zbigniew to surrender. Following this Zbigniew was banished from the country altogether. From then forward Bolesław III was the sole lord of the Polish lands, though in fact his over-lordship began in 1107 when Zbigniew paid him homage as his feudal lord.

Later on in 1108, Bolesław III, once again attacked Bohemia, as his ally King Coloman of Hungary was under attack by the combined forces of Holy Roman Empire and Bohemia. Another reason for the expedition was the fact that Svatopluk, who owed Bolesław III his throne, did not honor his accord in which he promised to return Silesian cities seized from Poland (Raciborz, Kamieniec, Kozle among others) by his predecessors. Bolesław III began to back Borivoj II of Bohemia and aimed to bring him back in power. This attempt was not successful.

In response to Bolesław’s aggressive foreign policy, German king and Holy Roman Emperor Henry V undertook a punitive expedition against Poland in 1109. In the resulting Polish–German War, German Forces were assisted by Czech warriors provided by Svatopluk the Lion, Duke of Bohemia. The alleged reason for war was the issue of Zbigniew and his pretensions to the Polish throne. The military operations mainly took place in southwestern Poland, in Silesia, where Henry V’s army laid siege to major strongholds of Głogów, Wrocław and Bytom Odrzanski. The heroic defense of towns, where Polish children were used as human shields by the Germans, in large measure contributed to the German inability to succeed. At this time along with the defense of towns, Bolesław III Wrymouth was conducting a highly effective guerilla war against the Holy Roman Emperor and his allies, and eventually he defeated the German Imperial forces at the Battle of Hundsfeld on 24 August 1109. In the end Henry V was forced to withdraw from Silesia and Poland altogether.

A year later in 1110 Bolesław III undertook an armed expedition against the German ally, Bohemia. His intention was to install yet another pretender on the Czech throne, Sobeslaus I. During the campaign Bolesław won a decisive victory against the Czechs at the Battle of Trutina. However, following the battle he ordered his forces to withdraw further attack against Bohemia. The reason for this is speculated to be the unpopularity of Sobeslaus I among Czechs as well as Bolesław’s unwillingness to further deteriorate his relations with the Holy Roman Empire. In 1111 a truce between Poland and the Holy Roman Empire was signed which stipulated that Sobeslaus I would be able to return to Bohemia while Zbigniew would be able to return to his native Poland. That same year Zbigniew was received back in Poland and furnished with a grant. A year later in 1112 he was blinded on Bolesław’s orders.

Excommunication

The blinding of Zbigniew caused a strong negative reaction among Bolesław's subjects. It should be noted that unlike for instance in the east, blinding in medieval Poland was not accomplished by burning the eyes out with a red hot iron rod or knife, but a much more brutal technique was employed. The condemned man's eyes were pried out using special pliers. The convict was made to open his eyes and if he did not do so, his eyelids were torn out along with his eyeballs. Upon learning of Bolesław's act Martin I, Archbishop of Gniezno and primate of Poland, who was a strong supporter of Zbigniew, excommunicated Bolesław III Wrymouth for committing the crime against his half-brother. Archbischop Martin also exempted all of his subjects from the obligation of obedience to Duke Bolesław III. The Duke was faced with a real possibility of uprising, of the sort that deposed Bolesław the Bold. Seeing his precarious situation Bolesław III sought the customary penance that would reconcile the high priesthood. According to Gallus Anonymus, Bolesław first fasted for forty days, replaced his fine clothes with a hair cloth and slept "in ashes".[48] He also sought and received forgiveness from his brother Zbigniew. This however, was not enough to convince the high echelons of the church and lift the excommunication. The Duke was compelled to undertake a pilgrimage to Hungary to the monasteries of Saint Giles and Saint Stephen I in Székesfehérvár. It must be noted that the pilgrimage to the Abbey of Saint Giles also had a political goal; Bolesław strengthened his ties of friendship and alliance with the Arpad dynasty the ruling house of Hungary. Following his return to Poland, Bolesław III traveled to Gniezno to pay further penance at the tomb of Saint Adalbert. He also bestowed numerous costly gifts on the poor and clergy throughout his penance. Due to his dedication the excommunication was finally lifted.

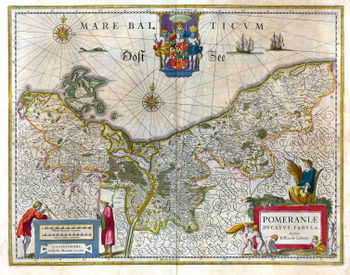

Conquest and conversion of Pomerania

The issue of conquest of Pomerania had been a lifelong pursuit for Bolesław III Wrymouth. His political goals were twofold; first - to strengthen the Polish border on the Noteć river line, second - to subjugate Pomerania with Polish political overlordship but without actually incorporating it into the country with the exception of Gdansk Pomerania and a southern belt north of river Noteć which were to be absorbed by Poland. By 1113 the northern border has been strengthened. The fortified border cities included: Santok, Wieleń, Nakło, Czarnków, Ujście and Wyszogród. Some sources report that the border began at the mouth of river Warta and Oder in the west, ran along the river Noteć all the way to the Vistula river.[49]

Before Bolesław III began to expand in the Pomerelia, he normalized his relations with his southern Bohemian neighbors. This took place in 1114 at a great convention on the border river Nysa Kłodzka. Participants included Bolesław III himself, as well as Bohemian dukes of the Premyslid line: Vladislaus I, Otto II the Black and Sobeslaus I. The pact was sealed by marriage of the then widower Bolesław III with the sister of the wife of Vladislaus I, Salomea of Berg.

In 1119 Bolesław III recaptured the territories of Gdansk Pomerania. During his Pomeranian campaign a rebellion by count palatine Skarbmir of the Abdaniec clan began. The rebellion was quelled by the prince in 1117 and the mutinous nobleman was blinded as punishment. He was replaced as count palatine by Piotr Wlostowic of the Labedz clan. In 1121 combined forces of Pomeranian princes Wartislaw I and Swantopolk I were defeated by Poles at the battle of Niekładź. From then on Bolesław ravaged Pomerania, destroyed native strongholds, and forced thousands of Pomeranians to resettle deep into Polish territory. The Duke’s further expansion was aimed towards Szczecin. The Polish ruler realized that Szczecin was a strong fort, well defended by the natural barrier of the Oder river as well as by well-built fortifications. The only way to approach the walls was through the frozen waters of a nearby swamp. Taking advantage of element of surprise Bolesław III launched his assault from precisely that direction, and took control of the city. Much of the population was put to the sword which motivated the remaining populace to subordinate to the Polish monarch.[50] In the years 1121-1122 Pomerania became a Polish fief and a local strongman, Duke Wartislaw I swore feudal allegiance to the Polish monarch and undertook to pay a yearly tribute of 500 marks of silver to Poland[51](One mark of silver was equal to 240 denarii.[52]) Wartislaw I also promised military aid to Poland at Bolesław’s request. In subsequent years the tribute was reduced to 300 marks.

In order to make Polish and Pomeranian ties stronger, Bolesław III organized a mission to Christianize the newly acquired territory. The Polish monarch understood that the Christianization of the conquered territory would be an effective means of strengthening his authority there. At the same time the Bolesław III wished to subordinate Pomerania to the Gniezno archbishopric. Unfortunately first attempts made by unknown missionaries did not make the desired progress. Another attempt, officially sponsored by the Polish prince, and led by Bernard the Spaniard who traveled to Wolin, has ended in another failure.[53] The next two missions were carried out in 1124-1125 and 1128 by Bishop Otto of Bamberg. Following an accord made between Duke Bolesław and Wartislaw I, Otto set out on a first stage of Christianization of the region. He was accompanied throughout his mission by the Pomeranian Duke Wartislaw I, who greeted the missionary on the border of his domain, in the environs of the city of Sanok. At Stargard the pagan prince promised Otto his assistance in the Pomeranian cities as well as help during the journey. He also assigned 500 armored knights to act as guard for the bishop’s protection. Primary missionary activities were aimed in the direction of Pyrzyce, then the towns of Kamien, Wolin, Szczecin and once again Wolin.[54] At Szczecin and Wolin which were important centers of Slavic paganism, opposition to conversion was particularly strong among the pagan priests and populace alike. Conversion was finally accepted only after Bolesław III lowered the annual tribute he imposed on the Pomeranians. Four great pagan temples were torn down and churches were built in their places, as was the usual custom of the Catholic Church.

In 1127 the first pagan rebellions began to take place. These were due to both the large tribute imposed by Poland as well as a plague that descended on Pomerania and which was blamed on Christianity. The rebellions were largely instigated by the old pagan priests, who had not come to terms with their new circumstances. Duke Wartislaw I confronted these uprisings with some success, but was not able to prevent several insurgent raids into Polish territory. Because of this Polish Duke Bolesław III was preparing a massive penal expedition that may have spoiled all the earlier accomplishments of missionary work by Bishop Otto. Thanks to Otto’s diplomacy direct confrontation was avoided and in 1128 he embarked on another mission to Pomerania. This time more stress was applied to the territories west of the Oder River, i.e. Usedom, Wolgast and Gützkow, which were not under Polish suzerainity.[55][56] The final stage of the mission retuned to Stettin (Szczecin), Wollin (Wolin) and Kammin (Cammin, Kamien). The Christianization of Pomerania is considered one of the greatest accomplishments of Bolesław’s III Pomeranian policy.

Once the missionary activities of Otto of Bamberg took root Bolesław III began to implement an ecclesiastical organization of Pomerania. Pomerelia was added to the Diocese of Włocławek, known at the time as the Kujavian Diocese. A strip of borderland north of Noteć was split between the Diocese of Gniezno and Diocese of Poznan. The bulk of Pomerania was however made an independent Pomeranian bishoporic, set up in the territory of the Duchy of Pomerania in 1140, after Bolesław had died in 1138 and the duchy had broken away from Poland.[55]

In 1135, Bolesław had accepted overlordship of Holy Roman Emperor Lothair III and in turn received his Pomeranian gains as well as the still undefeated Principality of Rügen as a fief.[55][57][58][59] Wartislaw I, Duke of Pomerania also accepted the Emperor as his overlord.[55] With Bolesław's death in 1138, Polish overlordship ended,[60] triggering competition of the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark for the area.[55]

Church foundations

Duke Bolesław III was not only a predatory warrior but also a cunning politician and a diplomat. He was also a patron of cultural developments in his realm. Like most medieval monarchs, he founded several churches and monasteries most important of which are the monastery of Canons regular of St. Augustinein Trzemeszno, founded in the 12th century, and a Benedictine monastery of Holy Cross atop the Łysa Góra which was founded in place of an ancient pagan temple. Also the first major Polish chronicle written by one Gallus Anonymus dates back to the reign of Duke Bolesław III.

Last years

In 1135, Bolesław finally gave his belated oath of allegiance to the new Emperor Lothair II (Lothar von Supplinburg), and paid twelve years past due tribute. The emperor granted Bolesław parts of Western Pomerania and Rügen as fiefs, however the emperor was not in control of these areas and Bolesław also failed to subdue them.

Bolesław also campaigned in Hungary 1132–1135, but to little effect.

Statute of succession

Before his death in 1138, Bolesław Wrymouth published his testament dividing his lands among four of his sons. The "Senioral Principle" established in the testament stated that at all times the eldest member of the dynasty was to have supreme power over the rest and was also to control an indivisible "senioral part": a vast strip of land running north-south down the middle of Poland, with Kraków its chief city. The Senior's prerogatives also included control over Pomerania, a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. The "senioral principle" was soon broken, leading to a period of nearly 200 years of Poland's feudal fragmentation.

Marriages and issue

By 16 November 1102 Bolesław married Zbyslava (b. ca. 1085/90 - d. ca. 1112), daughter of Grand Duke Sviatopolk II of Kiev. They had three children:

- Władysław II the Exile (b. 1105 - d. Altenburg, 30 May 1159).

- A son (b. ca. 1108 - d. aft. 1109).

- A daughter [Judith?] (b. ca. 1111 - d. aft. 1124), married in 1124 to Vsevolod Davidovich, Prince of Murom.

Between March and July of 1115, Bolesław married his second wife, Salomea (b. bef. 1101 - d. 27 July 1144), daughter of Henry, Count of Berg-Schelklingen. They had thirteen children:

- Leszek (b. 1115 - d. 26 August bef. 1131).

- Ryksa (b. 1116/17 - d. aft. 25 December 1156), married first ca. 1127 to Magnus the Strong, King of Västergötland; second on 18 June 1136 to Volodar Glebovich, Prince of Minsk and Hrodno; and third in 1148 to King Sverker I of Sweden.

- A daughter (b. bef. 1119 - d. aft. 1131), married in 1131 to Conrad, Count of Plötzkau and Margrave of Nordmark.

- Sophie (b. 1120 - d. 10 October 1136).

- Casimir (b. 9 August 1122 - d. 19 October 1131).

- Gertruda (b. 1123/24 - d. 7 May 1160), a nun at Zwiefalten (1139).

- Bolesław IV the Curly (b. ca. 1125 - d. 3 April 1173).

- Mieszko III the Old (b. 1126/27 - d. Kalisz, 13 March 1202).

- Dobroniega (b. 1129 - d. by 1160), married ca. 1142 to Dietrich I, Margrave of Lusatia.

- Judith (b. 1130 - d. 8 July 1175), married on 6 January 1148 to Otto I, Margrave of Brandenburg.

- Henry (b. 1131 - d. 18 October 1166).

- Agnes (b. 1137 - d. aft. 1182), married in 1151 to Mstislav II, Prince of Pereyaslavl and Grand Prince of Kiev since 1168.

- Casimir II the Just (b. 1138 - d. 5 May 1194).

See also

- Piast dynasty

- History of Poland (966-1385)

External links

References

- ↑ Oswald Balzer was in favor of 1086 as the year of birth, in bases of the records of the oldest Polish source: Roczniki Świętokrzyskie and Rocznik kapitulny krakowski; O. Balzer: Genealogia Piastów, p. 119.

- ↑ K. Jasiński: Rodowód pierwszych Piastów, Poznań: 2004, pp. 185-187. ISBN 83-7063-409-5.

- ↑ O. Balzer's genealogy doesn't mention the coronation of Vratislav II, but he places the traditional date given by the chronicles of Cosmas of Prague (15 June 1086) to the coronation of the first King of Bohemia; O. Balzer: Genealogia Piastów, p. 108. V. Novotny indicates that the Synod of Mainz took place in late April or May 1085; V. Novotny: Ceske dejiny. Diiu I cast 2. Od Bretislava I do Premysla I, Prague 1912, p. 245. He believes that Vratislav II's coronation as King of Bohemia and Poland took place on 15 June 1085, after the synod, and not in 1086, as reported by O. Balzer and Cosmas of Prague. Compare to W. Mischke: Poland Czech kings crown (in Polish) [available August 24, 2009], pp. 11-12, 27-29.

- ↑ Cosmas of Prague affirmation about the coronation of Duke Vratislav II as King of Poland is disputed by many historians. Medievalists consider it a mistake of the chronicler; G. Labuda: Korona i infuła. Od monarchii do poliarchii, Kraków: 1996, p. 13. ISBN 83-03-03659-9. A detailed argument over the supposed coronation of Vratislav II was presented by W. Mischke: Poland Czech kings crown (in Polish) [available August 24, 2009], pp. 11-29. M. Spórna and P. Wierzbicki believe that message of Cosmas is authentic. As King of Poland, Vratislav II stemmed from the emperor's claim to sovereignty over the Polish homage (fief indirect, second-degree); M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego, p.496.

- ↑ R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego, p. 353; M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 175.

- ↑ R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, p. 130.

- ↑ O. Blazer didn't include the mother of Zbigniew in the list of Duke Władysław I's wives. Jan Wagilewicz named her Krystyna; O. Balzer: Genealogia Piastów, p. 107. T. Grudziński believes that by 1080, Duke Władysław I was still unmarried. In contrast, many historians stated the Zbigniew's mother was the first wife of Duke Władysław I; K. Jasiński: Rodowód pierwszych Piastów, Poznań 2004, p. 164. ISBN 83-7063-409-5. Today it is widely accepted that the mother of Zbigniew was Przecława, a member of the Prawdzic family; see A. Nawrot (ed.): Encyklopedia Historia, Kraków 2007, p. 738. ISBN 978-83-7327-782-3.

- ↑ M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 178.

- ↑ Strengthening the Polish situation in the first years of the rule of Władysław I, he could refuse to pay tribute to Bohemia for Silesia. M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 179.

- ↑ The cult of Saint Giles began to expand rapidly in Europe during the first half of the 11th century. Polish lands went through the clergy, or pilgrims going to Saint-Gilles and Santiago de Compostella; K. Maleczyński: Bolesław III Krzywousty, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Władysław, by the grace of God Duke of the Polans, and Judith, his legitimate wife, send to Odilon, the venerable Abbot of Saint Giles, and all his brothers humble words of profound reverence. Learned that Saint Giles was superior to others in dignity, devotion, and that willingly assisted [the faithful] with power from heaven, we offer it with devotion this gifts for the intentions of had children and humbly beg for your holy prayers for our request. Gallus Anonymus, Cronicae et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum, vol. I, cap. XXX, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ 12th century chronicles mentions that at the coffin of St. Giles was a golden image of some form. J. ed. Vielard: La guide du pèlerin de Saint-Jacques de Compostelle, XII-wieczny przewodnik pielgrzymów ST. Gilles, St. Giles 1938; M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 179.

- ↑ K. Maleczyński: Bolesław III Krzywousty, p. 13.

- ↑ M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego, p.353.

- ↑ P. Ksyk-Gąsiorowska: Zbigniew, [in]: Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny, Kraków 1999, p. 72. ISBN 83-08-02829-2.

- ↑ R. Grodecki believes that the banishment of Zbigniew to Quedlinburg Abbey was thanks to Count Palatine Sieciech and Duchess Judith-Sophia; R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, p. 129.

- ↑ The opposition gathered in two camps, with Mieszko Bolesławowicu and Zbigniew, and claimed the legal recognition of both princes as pretenders to the throne; S. Szczur: Historia Polski – średniowiecze, p. 117.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, p. 128.

- ↑ K. Maleczyński: Bolesław III Krzywousty, p. 30.

- ↑ S. Szczur believes that the plans of Sieciech to impose the Polish administration by force allowed the rapid integration with Poland; S. Szczur: Historia Polski – średniowiecze, pp. 117-118.

- ↑ M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego, p. 445.

- ↑ M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 182.

- ↑ K. Maleczyński: Bolesław III Krzywousty, p. 26.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, p. 129.

- ↑ In the return of Zbigniew to Poland also involved Bretislaus II, Duke of Bohemia; M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, pp. 182-183.

- ↑ L. Korczak: Władysław I Herman [in]: Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny, Kraków 1999, p. 65. ISBN 83-08-02829-2.

- ↑ The release of Zbigniew took place during the consecration of Gniezno Cathedral; M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, p. 183.

- ↑ R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, p. 131.

- ↑ M. Bałaban: Historia i literatura żydowska ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem historii Żydów w Polsce, vol. I-III, Lwów 1925, p. 72.

- ↑ According to K. Maleczyński, Bolesław III and Zbigniew received separated districts already in 1093, and the first actual division of the Principality took in a few years later; K. Maleczyński: Bolesław III Krzywousty, pp. 34-35. In 1093, Władysław I admitted, inter alia, to give Kłodzko to Bolesław III (hypothesis presented by G. Labuda). R. Gładkiewicz (ed.): Kłodzko: dzieje miasta. Kłodzko 1998, p. 34. ISBN 83-904888-0-9.

- ↑ S. Szczur: Historia Polski – średniowiecze, p. 119.

- ↑ Zbigniew he should rule over Mazovia after the death of his father. This district, along with the towns inherited by Bolesław III (Wroclaw, Krakow and Sandomierz) had to ensure the future control and full authority over the state. R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, pp. 131-132.

- ↑ Historians presented different views on the division of the country. R. Grodecki think that first division took place during the reign of Władysław I (in the years 1097-1098) and the second after his death in 1102, under the arbitration of Archbishop Martin I of Gniezno. R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej, vol. I, pp- 131-135. G. Labuda believes that the division occurred around 1097, but only when Bolesław III had completed 12 years. G. Labuda: Korona i infuła. Od monarchii do poliarchii, Kraków:1996, pp. 16-69. ISBN 83-03-03659-9. K. Maleczyński placed the date of the first division around 1099. J. Wyrozumski: Historia Polski do roku 1505, Warszaw 1984, p. 101. ISBN 83-01-03732-6.

- ↑ S. Szczur: Historia Polski – średniowiecze, p. 120.

- ↑ These events are described, inter alia, in the publication of Zdzisław S. Pietras, "Bolesław Krzywousty". See Z. S. Pietras: Bolesław Krzywousty, Cieszyn 1978, pp. 45-60.

- ↑ Stanisław Szczur: Historia Polski: Średniowiecze – Krakow, 2008, pp.121

- ↑ K. Maleczyński:Bolesław Krzywousty: Zarys Panowania, Krakow: 1947, pp. 53-56.

- ↑ Pawel Jasienica: Polska Piastów, Warszawa, 2007 pp. 117

- ↑ M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, Warszawa, 2008, pp. 194.

- ↑ M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, Warszawa, 2008, pp. 193.

- ↑ M. K. Barański: Dynastia Piastów w Polsce, Warszawa, 2008, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego. Krakow, 2003, pp. 62.

- ↑ M. Spórna, P. Wierzbicki: Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego. Krakow, 2003, pp. 62

- ↑ K. Maleczyński: Bolesław Krzywousty: Zarys Panowania, Krakow: 1947, pp. 65

- ↑ Z. S. Pietras: Bolesław Krzywousty. Cieszyn, 1978, pp. 90-91

- ↑ K. Maleczyński: Bolesław Krzywousty: Zarys Panowania, Krakow: 1947, pp. 68

- ↑ Gallus Anonymus Cronicae et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum

- ↑ R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej. T. I. S. 143.

- ↑ Baranowska: Pomorze Zachodnie – moja mała ojczyzna. Ss. 40-42.

- ↑ R. Grodecki, S. Zachorowski, J. Dąbrowski: Dzieje Polski średniowiecznej. T. I. pp. 144-145.

- ↑ A.Czubinski, J. Topolski: Historia Polski. Ossolineum 1989, pp. 39

- ↑ L. Fabiańczyk: Apostoł Pomorza. pp. 34-35

- ↑ O.Baranowska: Pomorze Zachodnie – moja mała ojczyzna. pp. 40-42

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 Kyra Inachim, Die Geschichte Pommerns, Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, p.17, ISBN 978-3-356-01044-2

- ↑ Norbert Buske, Pommern, Helms Schwerin 1997, p.11, ISBN 3-931185-07-9

- ↑ Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, ISBN 839061848: (German version, this book is also available in Polish)

-

- Quote p.43: "Als Bolesław 1135 in Merseburg vor dem Kaiser den Lehnseid ablegte, galt dieser [...] sogar Rügen, das nicht unterworfen worden war". "The oath Bolesław gave to the emperor in Merseburg in 1135 was [..] even for Rügen, which had not been subdued."

-

- ↑ Norbert Buske, Pommern, Helms Schwerin 1997, pp.11,12, ISBN 3-931185-07-9

- ↑ Aleksander Gieysztor, Krystyna Cękalska, "History of Poland", PWN, Polish Scientific Publishers, 1979, pg. 67:" Rügen, on which the Polish duke aimed to establish himself against Danish influence."

- ↑ Kyra Inachim, Die Geschichte Pommerns, Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, p.17, ISBN 978-3-356-01044-2: "Mit dem Tod Kaiser Lothars 1137 endete der sächsische Druck auf Wartislaw I., und mit dem Ableben Boleslaw III. auch die polnische Oberhoheit."

|

Bolesław III Wrymouth

Piast Dynasty

Born: 20 August 1086 Died: 28 October 1138 |

||

| Preceded by Władysław I Herman |

Duke of Poland with Zbigniew until 1107 1102–1138 |

Succeeded by Władysław II the Exile Bolesław IV the Curly Mieszko III the Old Henryk |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||